In this blog, we will continue to discover a little more what a shearwater is capable of. In my first blog post about the different aspects of a shearwater’s life, we learnt about their incredible capabilities at sea by tracking them during the breeding season. In the second blog, we travelled with them flying over the waves and learnt about the way they could navigate in the open and featureless ocean and yet still succeed to come home to their colony in time for the breeding season and after each fishing trip.

Like every year, between February and July, Yelkouan Shearwaters have another breeding season in Malta. During these long months, they will go back and forth at sea, to the Gulf of Gabes in Tunisia or to southeast Italy to catch their food and feed their one and only chick each year.

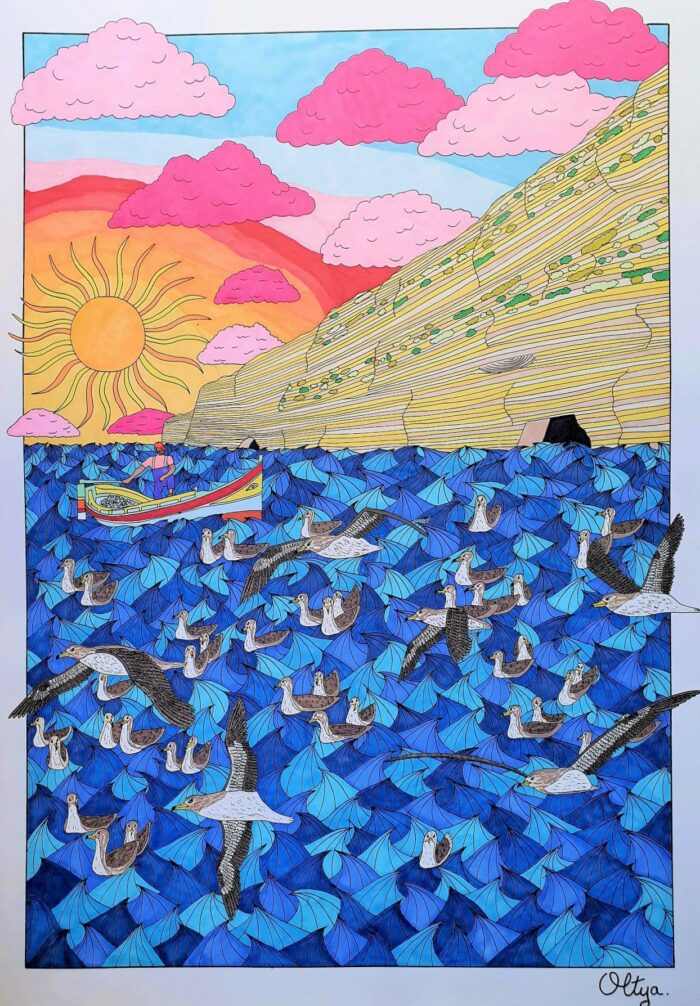

Shearwaters exhibit other behaviors that only a few seabirds adopt. When darkness is about to fall, they gather on the sea, forming large groups of hundreds, even thousands of individuals, floating all together not too far from the colony. This behaviour is referred to as “rafting”, and it is done before going back inside their burrow in the colony and relieving the partner from the task of incubating the egg or keeping the chick warm during the first days. At first glance, it wouldn’t seem that this activity is done for any particular reason! But of course, this is not the case.

We saw in a previous blog post that the longest trip made by a Yelkouan Shearwater was 11 days. After a long trip away from home, would you not just want to go directly inside, feed your chick and rest from your journey? Why do they adopt this behaviour? Seabirds are living an amazing life, and witnessing this rafting behavior is a unique show that only nature can give. In this blog post, we will take a look of what is happening during that time, and we will take a closer look into the mind and instinct of these magnificent birds.

Security in numbers

Shearwaters have an incredible capability to follow smells. It means that they can navigate in complete darkness without relying on their sight, making it easy for them to find their way to the colony at night. During daytime, seabirds are wandering the sea looking out for fish, squids or crustaceans. When close to their colony, they will raft together waiting for darkness before entering the colony. In fact, the vast majority of burrow nesting tubenose seabirds from the Procellariiformes order only return in the colony when the light level falls under a certain level and again leave before the sun rises to stay away of diurnal avian predators (Miles et al., 2013).

Through the Selfish Herd Principle (Hamilton., 1971), temporary animal aggregations not as a consequence of large amount of resources available like food, is beneficial to individuals by reducing personal predation risk. By forming large groups at sea, close to the coast, they are actually avoiding predation. Shearwaters are assessing the threat before returning to their burrow and feeding the chick. For example, in Malta, the Yellow-legged Gull wouldn’t hesitate to attack any shearwater flying near the cliff during daytime. The same is the case for predation by birds of prey, such as the Peregrine Falcon, which is known to hunt shearwaters.

The strategy of forming large groups of the same species is well known in the natural world as a means of defense. The predators are confused by the raft, and by adopting this behavior, shearwaters are finding safety in numbers.

Shearwaters have always chosen nesting grounds where coming back at night they would be safe from predators and other threats. Sadly, it is not the case in a lot of places anymore. When coming back on land, even during the night under the cover of darkness, nowadays, they remain threatened. Invasive species active during the night, like rats, mice and cats pose a serious threat by predating eggs, chicks and adults. One mission of BirdLife Malta’s seabird team is to control those invasive populations near the shearwater colonies and improve the breeding success of each colony.

The moonlight intensity also influences the rafting behavior (Rubolini et al., 2014). Moonlight improves foraging efficiency of predators, so shearwaters will wait until the light level is acceptable to return to the colony or stay at sea to improve their foraging success. Strong moonlights will play on the raft intendance as it gives the opportunity to increase the foraging success out at sea. This means that shearwaters can anticipate, to an extent, the moon phase when leaving the colony and returning from a foraging trip t. In addition, forming large groups at a safe distance from danger provides opportunities for the birds to engage in other important social interactions.

Sharing time

Most seabird species group themselves in colonies during the breeding season. What brings them together during the crucial moment of the breeding season?

When Yelkouan Shearwaters are aggregating in front of the cliff of Rdum tal-Madonna or Majjistral, they are doing more than just waiting for darkness to fall. During this dense aggregation on the surface, it is time for social interactions like exchange of information as explained in the Information Centre Hypothesis (Ward et al., 1973).

Seabird colonies function as information centers where individuals can exchange information widely and can, for example, improve foraging success (Richard et al., 2019). In one study about the rafting behavior in shags, biologists showed that birds form a compass raft as an orientation signaling function to identify the best foraging routes from the colony (Weimerskirch et al., 2010). The raft is continuously adjusting to indicate the largest returning columns of seabird, giving the direction of the location of good foraging patches. Shearwaters might have an equivalent technique to increase their foraging success. A raft is a social opportunity for information exchange amongst individuals of a colony. Shearwaters will raft for longer periods both before and after visiting their burrows, which is associated with preening of their feathers. After passing a moment in the dust of the burrow or after a long and exhausting foraging trip travelling hundreds of kilometers, they take the time to clean themselves and to preserve their plumage, as seen in the Northern Gannet (Thiebault et al., 2014). The rafting behaviour is well-studied and yet, it is difficult to understand the true nature of their social interaction. As humans, we see the world through our own perspective, but it is difficult to imagine the world through the senses of a seabird. Is it possible to unlock all the mysteries of those wonderful creatures?

An important time for shearwaters

As described above, it is evident that rafting behaviour is an important strategy for shearwater species.

For biologists, it is important to understand more about the different zones where shearwaters are rafting, in order to afford greater protection in these areas. It is logical that activities such as boating, excessive lights and sounds could affect this behavior, so these areas must be managed to minimize disturbance. Seabirds are threatened on land by invasive species and habitat loss, and also at sea by food scarcity due to climate change and industrial overfishing but also by accidental bycatch and increased stress due to boat disturbance and noise pollution.

By tracking movements of the Yelkouan Shearwater, the BirdLife Malta seabird team aims to identify important areas for rafting and foraging. The findings could help with informing marine spatial planning and improve management within Marine Protected Area boundaries.

In Malta we are lucky enough to have the opportunity to observe this rafting behaviour every year. Birdlife Malta’s organizes Shearwater Boat Trips in July to observe the raft of the Scopoli’s Shearwaters at the beautiful scenery of Ta’ Ċenċ cliffs during sunset. It is definitely one of the most spectacular natural wonders we can enjoy on our islands, and we invite you to join us! Follow Birdlife Malta on social media to find out more about these trips, and about these incredible Yelkouan Shearwaters!

Bibliography

Hamilton WD. 1971. Geometry for the selfish herd. Journal of Theoretical Biology 31:295-311

Miles WTS, Parsons M, Close AJ, Luxmoore R, Furness RW. 2013. Predator-avoidance behaviour in a nocturnal petrel exposed to a novel predator. Ibis 155:16-31

Richards C, Padget O, Guilford T, & Bates AE. 2019. Manx shearwater (Puffinus puffinus) rafting behaviour revealed by GPS tracking and behavioural observations. PeerJ 7:e7863

Rubolini, D., Maggini, I., Ambrosini, R., Imperio, S., Paiva, V. H., Gaibani, G., … Cecere, J. G. 2014. The Effect of Moonlight on Scopoli’s ShearwaterCalonectris diomedeaColony Attendance Patterns and Nocturnal Foraging: A Test of the Foraging Efficiency Hypothesis. Ethology, 121(3), 284–299.

Thiebault A, Mullers R, Pistorius P, Meza Torres MA, Dubroca L, Green D, Tremblay Y. 2014. From colony to first patch: processes of prey searching and social information in Cape Gannets. The Auk 131:595-609

Ward P, Zahavi A. The importance of certain assemblages of birds as information-centers for food-finding. Ibis. 1973. ;115:517–534

Weimerskirch H, Bertrand S, Silva J, Marques JC, Goya E. 2010. Use of social information in seabirds: compass rafts indicate the heading of food patches. PLOS ONE 5:e9928 DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0009928.

By Marc Schruoffeneger, Seabird Conservation Assistant

Marc Schruoffeneger is an Erasmus+ volunteer following a European Solidarity Corps programme