Long before humans developed technology capable of creating artificial light, almost all life on earth had evolved with a constant and recurring cycle of day and night, save for species like those found dwelling in the deepest depths of our oceans. After millennia of being exposed to this strong and global cue, numerous essential biological processes of animals, plants, fungi, bacteria and even certain viruses depend on this natural phenomenon. The consequences of this cycle being disrupted can be severe and even fatal.

Long neglected as an area of research, light pollution and its effects have become the focus of numerous studies from the level of individual organisms to entire ecosystems. There is little good news in the results. One study shows that 80% of the world now lives under light-polluted skies and the Milky Way is hidden from one-third of humanity and all the wildlife that live alongside us [1]. Now, many of us may not care that we cannot see the stars, after all humans rarely need to use the stars to navigate anymore. However, stars remain an important navigational cue for many organisms from dung beetles to harbour seals. Where the visibility of the night-sky is reduced, animals that depend on a celestial compass may struggle to continue normal behaviours such as foraging, migration and vocalizations.

A more lethal aspect of light pollution is associated with a process called phototaxis, or the movement towards a light source. A well-known story is that of the turtle hatchlings and promenade lighting. However, an equally lethal form has been recorded across North America. Large towns and cities littered with brightly-lit skyscrapers act as traps for migratory birds. Birds caught within the glare of urban areas are likely to collide with buildings – one estimate suggests that the number of avian deaths attributable to light pollution in North America alone could be between 365 to 988 million annually [2].

The situation is different in the Maltese Islands. Although migratory birds have indeed fallen victim to light pollution across the country, it is our breeding seabirds that are most threatened by light pollution. The Yelkouan Shearwater, Scopoli’s Shearwater and European Storm-petrel belong to a group of birds called the Procellariiformes. Intensely sensitive to artificial light at night, these birds are utterly dependent on darkness to survive. The artificial illumination of their breeding colonies prevents adult birds returning to their nest to care for their chick, for fear of predation. Where breeding colonies are perpetually brightened by light pollution, adults have little choice but to abandon their nest entirely. In this way, entire colonies are deserted as habitat quality is deteriorated. This has already occurred at historical seabird breeding colonies most notably at Anchor Bay and Ħal Far.

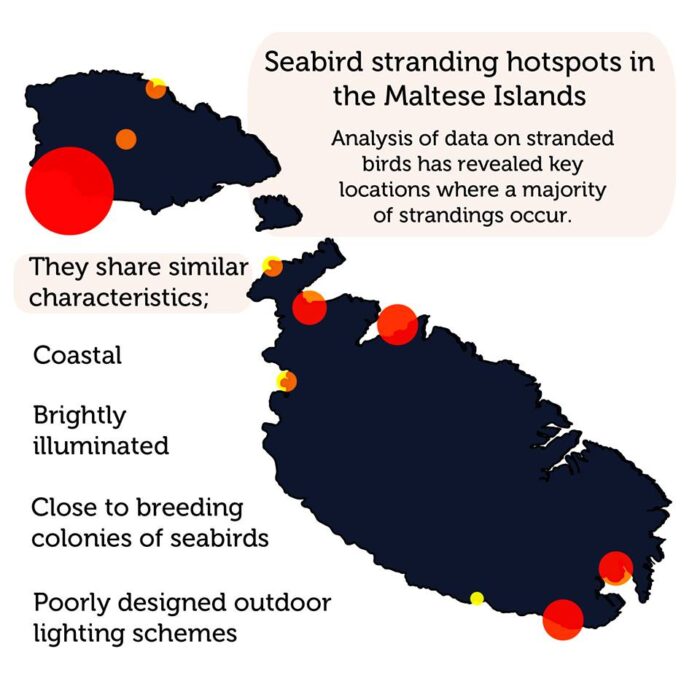

At the same time, predominantly young seabirds leaving their nests for the first time are disorientated by bright lights and end up stranded on land across Malta and Gozo. These stranding events almost exclusively occur within 10 localities identified as hotspots through our analysis of over 40 years of data. These hotspots are mainly urban, coastal, close to seabird breeding colonies and are amongst the most light-polluted sites in the Maltese Islands.

So far this year, a total of 23 birds have been recovered from across the Maltese Islands – 18 (78%) of these birds recovered from just six localities; Marsaxlokk/Freeport, Ħal Far, St. Paul’s Bay, Ċirkewwa, Victoria and Xlendi. It is important to keep in mind that this is the bare minimum – these 23 birds are the ones lucky enough to have been found and rehabilitated, many more are likely never found and die on land far from the safety of the sea.

We now have the means to mitigate light pollution through well-designed outdoor lighting schemes that provide a safe and secure urban environment for human use whilst keeping the ecological impacts to a minimum. If you are concerned about light pollution in your locality, please contact your local council and ask them what they are doing to reduce light pollution.

We would like to extend our most sincere thanks to all those who have helped us to recover stranded birds. Thanks to your efforts we have been able to successfully rehabilitate 21 of these birds and release them for a second chance at life.

By James Crymble, LIFE Arċipelagu Garnija Light Pollution Officer

References

[1] Falchi, F., Cinzano, P., Duriscoe, D., Kyba, C. C., Elvidge, C. D., Baugh, K., … & Furgoni, R. (2016). The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Science advances, 2(6), e1600377.

[2] Loss, S. R., Will, T., Loss, S. S., & Marra, P. P. (2014). Bird–building collisions in the United States: Estimates of annual mortality and species vulnerability. The Condor, 116(1), 8-23.