In the previous blogs we learnt about seabirds and their incredible abilities. Today the subject will be inversed, and we will shine some light on the people protecting and studying them.

The life of a seabird biologist is quite varied and can be quite atypical at times, adopting the same lifestyle as a seabird during the breeding season. We can mainly split their year into two different periods, the breeding season and the office season. There is no typical workday for a seabird biologist. Let’s put aside the office season with its statistics, reports, stakeholder engagement and other tasks. Let’s focus on how seabird biologists are studying seabirds and ensure that they have a viable future. We will try to gain a small insight into the life of a marine biologist.

Preparation

As the year finishes, the seabird team is already preparing for the next field season. It actually began directly after the end of the last one: a never-ending circle, like the eternal rhythm of the seasons.

A field season is quite intense, with a lot of wear and tear on equipment. Washing, cleaning, inventorying, maintaining…all the equipment is checked and taken care of to maximize its lifetime and, most important, to ensure the safety of the biologists for the season to come.

In the meantime, it is already time to plan the next breeding season, and to purchase all the necessary equipment. When the season hits, it is too late for that with everything else there is to do.

The start of the new field season

The first fieldwork tasks start during the month of February. It is the time to reinstall all the equipment in the different colonies to monitor seabirds after the winter storms.

Sadly, rats in search of food succeed to access the different colony sites during the winter months. Before shearwaters start laying eggs, for the perfect beginning of a new breeding season, biologists need to control the rat population. This period is stressful as rats can ruin the breeding season by predating eggs and future small chicks.

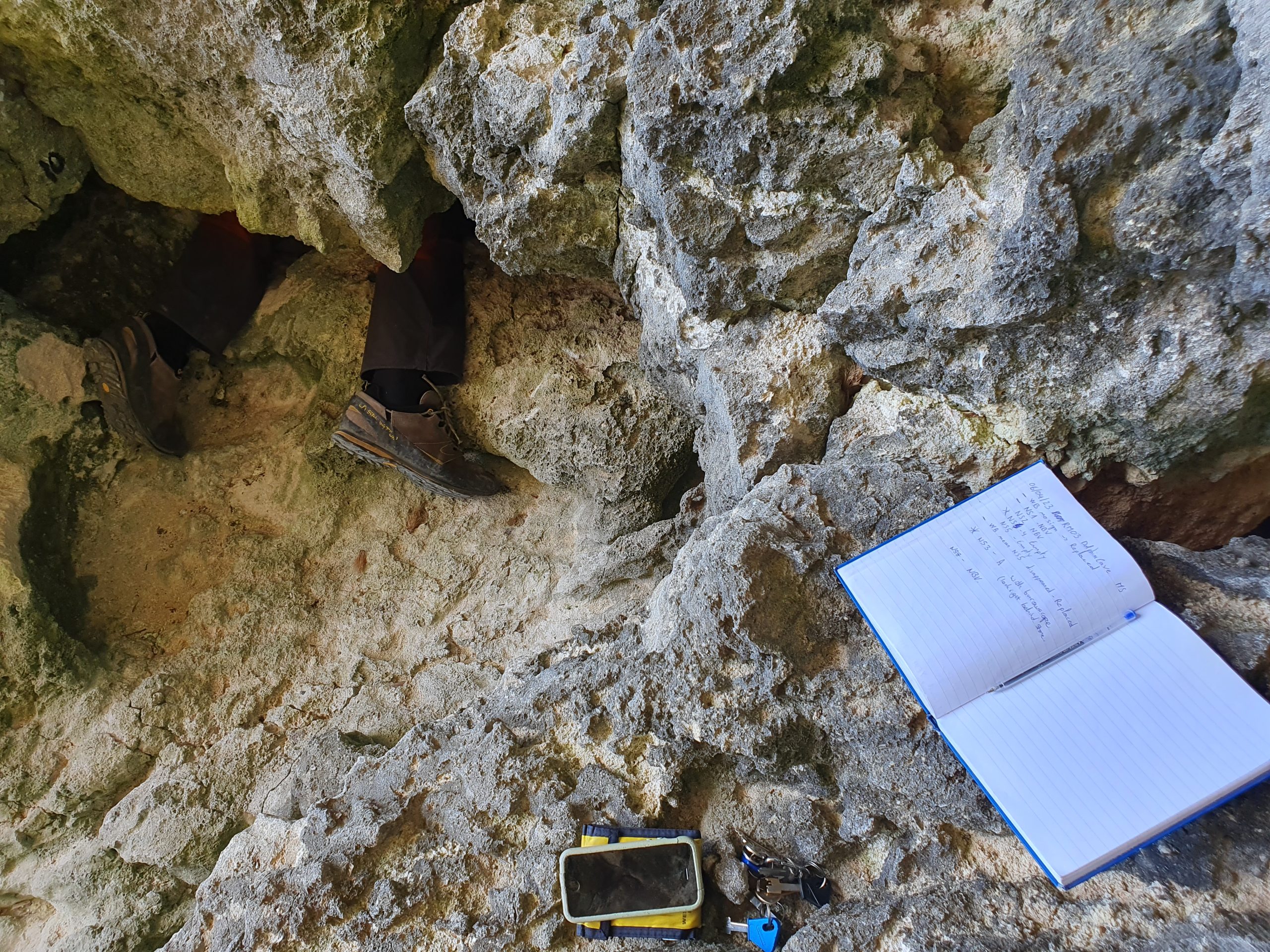

The main colonies will be equipped by camera traps at the entrance of the caves to monitor any rodent incursions and to estimate the seabird population per cave. Additionally, mechanical traps will be placed to counteract as quickly as possible any incursions. Around the colonies, non-toxic wax blocks with a chocolate taste will be placed to check for any rodent bites. Finally, lines of bait stations will lower the rodent density in the area on the periphery of the colony. Baiting requires carrying heavy boxes during long walks and a good mental map and orientation is needed to find each bait station. The process of checking bait stations happens at least once a month in every colony until fledglings leave the nest.

Despite all these efforts, rat predation can still happen. Another very important aspect remains: to improve waste management. The seabird team members are working ceaselessly with the competent stakeholders. It is so frustrating when you find an egg, or a little chick, predated during a survey.

During this first month, the team will have just enough time to gain back the reflexes from the last season. Just in time because the fieldwork pace is about to increase quite a bit.

Racing against time

One of the important data seabird biologists monitors is the breeding success. First, they need to visit all the nest sites in the different colonies to see which one is occupied this year. All nests have a special number to be able to follow from one year to the next.

In between the end of March and mid-July, to have accurate and usable data, the biologists need to visit at least three times each active nest until fledglings leave to wander the ocean. During these visits, scientists are monitoring the chicks’ stages to see how they are doing. With too many failures, there could be a problem in the environment.

Seabird biologists in Malta will access the colony by abseiling and scrambling, or by boat and kayak. Monitoring the nests means crawling into caves, often in very tight and narrow spaces. Pointy rocks, mud, sand and bird faeces are waiting for them. To be fair, it is an exciting aspect, full of hopes for a good breeding success, despite the fact that the repeating action makes it exhausting.

When the chick is almost ready to leave, fieldworkers ring it to give it a unique identity.

During the same period, they are doing Capture Mark Recapture. It is a way to evaluate the population number and adult survival rate. Basically, before sunset they are abseiling at a height of between four and 20 metres to the different colonies and positioning themselves in front of the caves to be monitored. Seabirds are still at sea, rafting, waiting patiently for darkness and biologists are waiting for them patiently too, in the dark until shearwaters land to feed their chick inside. Biologists need to be quick to catch them. Even if seabirds are clumsy on land, they are incredibly fast in entering their burrows. Once in the bag, researchers weigh them, ring them if they are new, or read the ring number. Once at the office they can check the ringing record and often find a very old bird or a bird ringed as a chick and never previously recaptured during the last five or so years.

Generally, the CMR finishes at around midnight depending on the seabird activity, and then it is time to abseil up, go back to their base, called normally an office, by van or boat to sort out and tidy the equipment. The biologists will finally be in their bed at around 2–3am. The field season is intense because they need to repeat this several days a week during several months. Always racing against time, the seabird team is also always fighting against the forecast as rainy or windy weather will stop any tentative of fieldwork. During this period if the weather is good, it doesn’t matter if it is the weekend or a public holiday, the biologists remain always available to go in the field.

Fieldwork can be hard at times and getting all the objectives checked every year is challenging. Yet, the breeding season is rewarding on many levels; biologists are able to monitor these elusive creatures that normally live far away from a land-based life. Moreover, spending so much time outside doing what they love improves their morale and physical abilities.

If you are interested in seabirds, there are some other blogs about their life to read on the BirdLife Malta website and the seabird team is organising a lot of events throughout the year to learn more about them. Maybe you can even get the opportunity to volunteer with the team!

Bonus part: a night on Filfla, the Maltese island full of wonders!

The fieldwork on Filfla is definitely something magical. This island is a nature reserve and possesses the biggest colony of Storm-petrels in the Mediterranean Sea. Around 8,000 pairs of Mediterranean Storm-petrels come back here to breed every year. These seabirds are incredible, they are just the size of a passerine and yet, they can live more than 30 years.

When biologists are reaching the island at the end of the afternoon, the first fieldwork task is to walk around the island to confirm again the absence of rats. An incursion on the rat-free island would be a catastrophe for the well-being of the seabird colony.

Finally, the hot sun is diving into the sea. It is the calm before the storm. From 9 pm to 4:30 am it is a continuous workflow. No time to rest as the number of seabirds being entangled in the mistnet never decreases. Each bird is carefully removed, ringed and gently released. The most important thing for biologists is not to harm the bird. The handling part needs to be quick and calm to not stress the bird too much. During the night, you could be jumping from boulder to boulder in order to reach the different parts of the net, sometimes in difficult and unbalanced positions.

As the night passes, the new and still unused bird rings never cease to disappear as they identify each bird with a new special identification number. On a typical night more or less 450 new birds are ringed, plus 200 or so recaptures from previous years. What a chance to be able to accomplish this work! So many of these amazing storm-petrels in one place is magical and reminds us of the importance of nature reserves especially free of rats.

Suddenly, as the night ends, the seabird activity drops. After an exhausting night of work, biologists are left with a feeling of gratitude and contentment but also the lack of activity reminds them that their body didn’t stop and is already feeling stiff. The tiredness is taking its toll, but there isn’t time to rest, yet. It is time to pack and wait for the boat to pick them up!

The darkness of the night is slowly making way to the warm sun which is waiting patiently to rise. As the sunlight progresses, the cold stones of Filfla are shining a beautiful golden color. Time to go home now and have a well-deserved rest!

By Marc Schruoffeneger, Seabird Research Officer

With support from the BirdLife Malta seabird team