In our previous seabird blog A journey with the Yelkouan Shearwater, we learnt about the incredible journey a Yelkouan Shearwater takes, time after time, with countless effort during the breeding season to succeed to raise its one and only chick. This time, we will try to discover a little more about their awesome capabilities.

Shearwaters belong to the order Procellariiformes, the same as petrels and albatrosses. In the blog we learnt that during the breeding season, the Maltese population of Yelkouan Shearwater is going several times to the Gulf of Gabes, in Tunisia, 400km away from the cliffs of Majjistral and Rdum tal-Madonna, back and forth in between three and 10 days. Other species are capable to travel even further. Have you ever wondered how those seabirds are able to travel so far, hundreds and hundreds of kilometres, and yet come back to the exact same point in the cliff crossing the featureless open ocean and thus, during the night?

It is very curious that, without compass, in an environment looking like a desert, made only of crests, waves, light and blue and yet, they still succeed to come home, time after time. It is hard to understand how a seabird is navigating at sea. When you are looking at them on land, they appear to be very clumsy, whereas at sea, we realise that they are not called seabirds for nothing.

The ocean is their environment, they are adapted to it and they perfectly know what they are doing to come home and to go to foraging grounds. More specifically, their tubenose is able to guide them following different scents. Studies are showing that they can follow smells as directions. It seems that shearwaters are able to build a mental map of the ocean based on smells, like memories! Shearwaters are able to remember memories of smells that pass through the air and adjust their direction to follow the right way home (Reynolds et al, 2015). To unlock and understand a part of the mystery and to think like a shearwater, we have to begin and go back at the start of the story.

Time to fledge!

It is not new that shearwaters are nesting in burrows and caves, which means that the chick will grow in a dark environment for the few first weeks of its life. During more than two months, the chick will develop its own sense to see the world around it. Its parents will feed it seafood and one odour particularly will take all its importance in the seabird’s life. The Dimethyl sulphide (DMS) is a chemical compound produced by seafood and phytoplankton. Growing up in that smell is making the chick sensitive to it and they are fully taking advantage of it. It is supposed to be a disagreeable odour, but for me, as a biologist studying seabirds, it is a smell full of memories, different species, places and stories. Since I began to work with seabirds, it is also, like for the shearwater, an attractive odour.

When the time arrive to fledge, they will wander the oceans during several years, waiting patiently for the time to being mature and being able to breed. Shearwaters can remember odour, and DMS is a smelling signal existing in the natural olfactory landscape of the ocean (Nevitt et al., 1995). During their exploration time, they are not blindly flying from one place to another. The seabirds are associating smells with food and remember places either as wind directions and doing so they are building a cognitive map of the ocean.

Coming back to land!

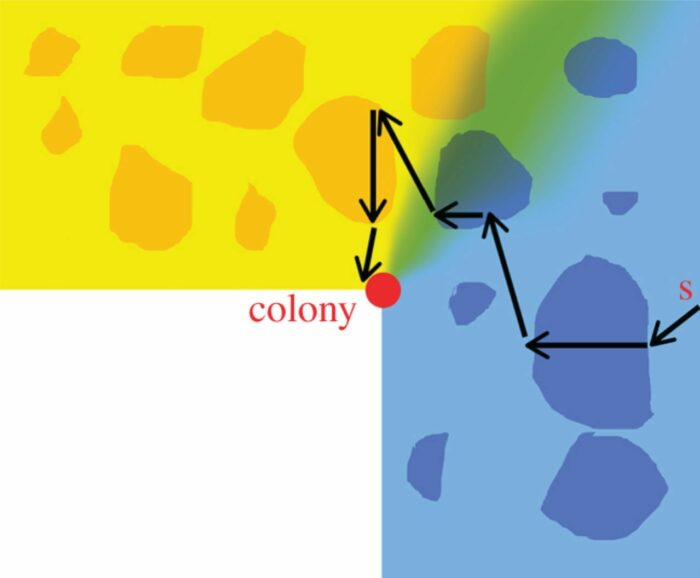

After the first years at sea, an average of five years for our Yelkouan Shearwaters, it is now time to go back home, where they hatched. Following the smell of their island, of their colony, where they grew up a long time ago. They will attempt to raise their own family! Alongside the other adults already breeding at the same colony since several years, they are coming back, crossing the vastness of the open ocean. But for them, they are not seeing the same world as us, the different concentration of DMS emission represents bathymetric element of the ocean, like seamounts or shelf breaks (Nevitt et al., 2005). They are cues in the marine seascape, something they can hold on to guide them. A problem persists, as you know, odour concentration can vary and be intermittent due to atmospheric turbulences. The smell indicating the right pathway might not be present.

In previous studies, scientists manipulated the sense of smell of Cory’s Shearwater and reported that the homing capacity (succeeding to come back home) was dramatically altered, while magnetically disturbed birds didn’t show any sign of having lost their navigational aptitudes. Their sense of smell is so precise that when the odours were continually present, they were using their special skills and were able to follow their map and fly unidirectionally. But when the odour passes under the detection level, the seabirds were lost, they changed course either because they became disorientated or trying to find their way to re-establish a contact with an odour they could remember (Gagliardo et al., 2013).

It is probable that is not the only way for them to build their map, and they are surely using landmarks and the flight of other birds too, in a way to adapt their flight patterns. In the shearwater world, they are masters of navigation and they evolve to survive and thrive in a rough and merciless environment. I believe that with time and a better understanding of their life, this will not be the last amazing thing to discover about them.

Life at sea

Imagine being a Yelkouan Shearwater, with your 85cm wingspan and yet flying in the vast and open ocean. To cover great distances like that, it is right to have some tricks for travelling. Seabirds are beings completely linked to the ocean, they evolved with it and are fully dependent of it. Even if they are flying, they are truly sea creatures, and the way they are navigating is proving it.

Growing up in the darkness of a burrow or a cave gives them the necessary sensitivity to the Dimethyl Sulphide and they are able to detect it at extremely low concentration. Add to that the capacity to remember from where this smell is coming from and you can imagine the navigational system of pelagic seabirds. An adaptable odour-map.

The capacity to smell tiny DMS concentration permits the Procellariidae to come home time after time during every trip of the breeding season. The odour is guiding them safely home and also to their favourite foraging location. They have this remarkable ability to identify precisely the location of their colony assembling a cognitive map of wind-borne odours. Just perfectly in time to feed the hungry chick!

Bibliography

Gagliardo A, Bried J., Lambardi P., Luschi P., Wikelski M. and Bonadonna F. ( 2013). Oceanic navigation in Cory’s Shearwaters: evidence for a crucial role of olfactory cues for homing after displacement. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 2796–2805.

Nevitt G. A., Veit R .R., Kareiva P. (1995). Dimethyl sulphide as a foraging cue for Antarctic procellariiform seabirds. Nature. 376:680–682.

Nevitt G. A. and Bonadonna F. (2005). Sensitivity to dimethyl sulphide suggests a mechanism for olfactory navigation in seabirds. Biol. Lett. 1, 303–305.

Reynolds Andrew M., Cecere Jacopo G., Paiva Vitor H., Ramos Jaime A. and Focardi Stefano (2015). Pelagic seabird flight patterns are consistent with a reliance on olfactory maps for oceanic navigation. Proc. R. Soc. B.2822015046820150468.

By Marc Schruoffeneger, Seabird Conservation Assistant

Marc Schruoffeneger is an Erasmus+ volunteer following a European Solidarity Corps programme