Bird migration is a phenomenon that is constantly being studied by researches all around the globe. In Malta we get many migrating birds both in spring and in autumn with most “European” birds making the trip from Europe to Africa and then back in a single year.

Observing migrating birds during the day is relatively easy but we know that most birds migrate at night. Very often we visit a site in the evening and we see no birds, we go there again in the morning and the place is full of birds. Migrating at night helps birds avoid predators such as birds of prey and also avoid the heat of the sun. But how can we observe birds migrating at night? We cannot see them, but we can listen to them. Not all species, but a good number of those that migrate at night, often call whilst on migration, especially if they are migrating in flocks. Furthermore, studies have shown that light pollution stimulates more nocturnal flight calls making Malta, an immensely light polluted island smack in the middle of the darkness of the surrounding Mediterranean Sea, an ideal place for listening to migrating birds at night.

A new technique, known as nocmigging, has been recently put to use by birders around Europe. Noc (nocturnal) migging (migration) is a relatively simple technique that enables the research of birds migrating at night. This involves leaving a sound recorder recording an entire night and then analysing the recording at a later stage. No extremely sophisticated or expensive equipment is needed but the more sensitive the microphone is and the better ability the setup has to filter out background noise (cars, waves, wind etc.) makes it more likely to pick up faint and distant calls of migrating birds.

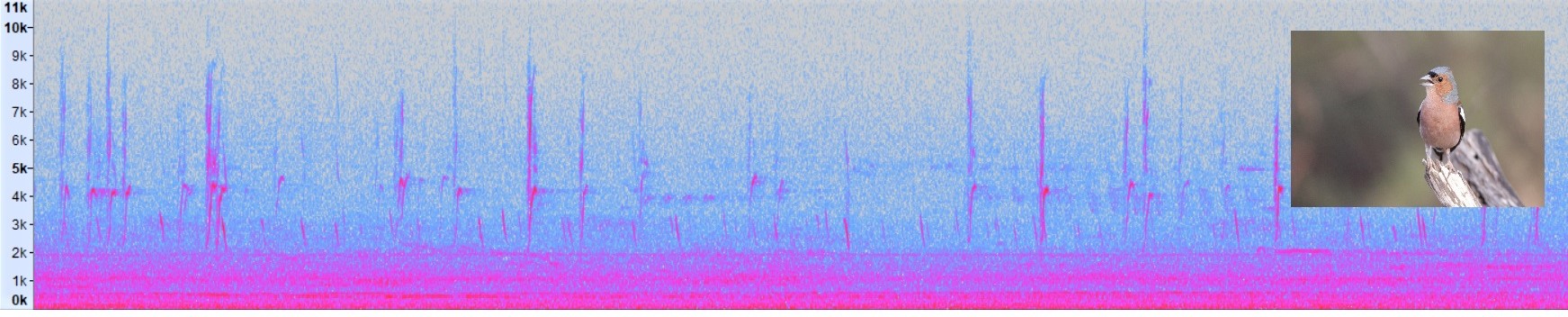

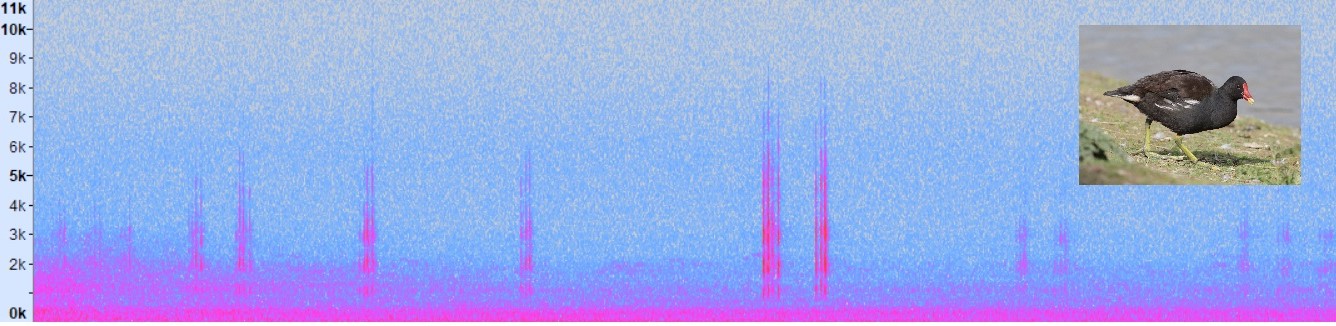

Analysing eight hours or more of mostly silence might seem like a huge task but such analysis is not done aurally but is done visually. What we do is generate a visual representation of the sound, known as spectrogram, using computer software (one example is Audacity, which can be downloaded for free) and then analyse it looking for shapes caused by bird sounds amongst other background noises. Once you spot a sound that looks like it comes from a bird, you listen to that sound (a call is often less than a second long) and identify it. With experience, an eight-hour night can be inspected in less than two hours. Once you get more and more experience, you start identifying birds from the sonogram itself, without the need to actually listen (still it’s always fun to listen).

For each migrating bird we record the date and time, the distance (whether close or far), the number of calls and if the bird sounds to be alone or in a group. A stereo microphone can also help determine the direction the bird was flying to.

I started nocmigging from my home town of Birkirkara less than a month ago. At first I was welcomed with a lot of skepticism by my fellow birding friends, and my family thought I had lost it when I walked in with a big microphone saying that I will be listening to birds at night, but as migration started to pick up, every night revealed amazing surprises of interesting species migrating over Malta. From one of the busiest town on the islands I already had 19 species of birds and spring migration has still a long way to go. I managed to record interesting species including seldom seen ones such as Moorhen, passerines which are rarely known to migrate at night in our region such as Chaffinches and birds which are typically only observed close to the shore like the Whimbrel.

The beauty of nocmigging is that it is a new and innovative way of studying birds. No one has ever done this study in Malta so every night I am learning new things and sharing with the local birding community. Some birds I expected to hear, like herons and waders, whilst others, like crakes and rails, left me amazed. Furthermore, nocmigging allows me to enjoy migration even when other commitments do not spare me enough daylight. Local interest is picking up and every day I get messages from friends asking me what I had “heard” the previous night. Hopefully we can turn this interest into a standardised study with nocmigging stations all across the islands in the near future.

As with everything, nocmigging has its own challenges. Noise is the biggest challenge, especially when it comes in the form of bird callers used illegally by trappers during the night. This makes nocmigging in rural areas around Malta very difficult as a night’s recording is filled with artificial bird sounds that may not be easy to separate from real birds.

By Nicholas Galea, BirdLife Malta bird ringer