Bird ringing plays an important part of the research and data collection BirdLife Malta carries out in the Maltese Islands. It involves the temporary capturing of wild birds in order to mark the birds with a uniquely numbered ring and take some biometrics (measurements) for scientific research. As part of BirdLife Malta’s ringing effort, ringers perform standardised ringing on the small island of Comino, where BirdLife Malta manages a bird observatory and ringing station, to monitor the migration of passerine birds (small birds) in spring and autumn. After spending 12 days ringing birds on the island of Comino, BirdLife Malta bird ringer Nicholas Galea reports on this year’s numbers.

Comino is an ideal location to monitor bird migration and to perform bird ringing in Malta for different reasons. Firstly, since it is a small, barren island, the ‘funnelling effect’ is often observed in the few areas with abundant vegetation. This means that birds landing on different parts of the island will eventually ‘funnel’ through the few vegetated valleys found on the island. Putting up nets in these areas, therefore, leads to a higher capture rate than in areas where birds can be ‘lost’ in the abundance of vegetation like in for example Buskett. Furthermore, Comino is one of the few sites in Malta where human disturbance is very low and is mostly contained within the area of Blue Lagoon. Birds are less likely to be flushed or scared away by humans and tend to stop for a longer time.

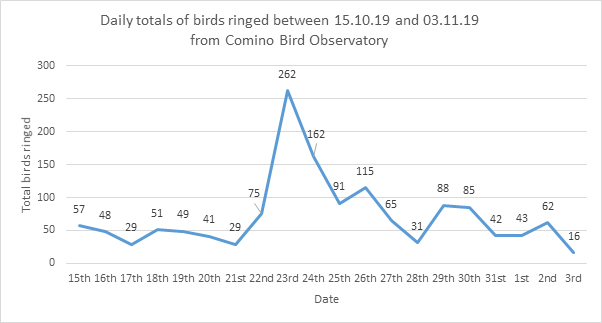

The autumn Comino ringing season this year was carried out for 20 days between the 15th of October and the 3rd of November. During these days, mist nets, used to capture birds as they fly between trees and bushes, are opened every day (when weather conditions permit and do not pose a threat to the safety of birds) from dawn to dusk. On Comino, ringing is standardised such that data collected is comparable from day to day and more importantly from year to year. Ways of ringing standardisation include ringing on the same days when compared to previous years, using the same number of nets, having nets in the same positions, etc. Factors such as weather conditions that have an effect on the effort made, and therefore on the number of birds ringed, are also recorded.

During this period, a total of 1,441 birds of 33 different species were ringed. Out of these, 66% or 949 were Robins. This is not a surprising percentage as over the years ringing has shown us that the Robin is actually a very common bird during migration in Malta. Furthermore, ringing, through the rates of re-capture of the same Robin specimens, also taught us that most of these birds keep going south and most likely winter in North Africa.

Out of these 1,441 birds, only 172 were identified as adult birds. This means that over 80% of the birds ringed were all young birds, i.e. birds born this year. This again is not a surprising statistic since in autumn the number of young birds greatly outnumbers that of adult ones since this migration period follows the breeding season. Through natural selection, the best (genetically speaking) specimens survive winter and spring migration and then breed in spring.

To determine the age of birds, ringers look at different criteria depending on the species of the birds. Some birds are straightforward to age from the colour of the plumage whilst others require examining of individual sets of feathers. For example, the main criteria for ageing a Robin include the colour of the interior, upper part of the bill, the shape (whether they are round or pointed) of the central tail feathers and the condition and freshness (abrasion of the feathers brought by contact with twigs etc., makes a feather look old) of old versus new feathers on the wing.

Apart from the regular species such as the Robin, Song Thrush, European Stonechat, Black Redstart, Blackcap and Common Chiffchaff which make up the bulk of the birds ringed every autumn on Comino, each year brings a number of rare birds, welcome rewards for the ringers’ efforts!

This year these rarer birds were in the form of a Moussier’s Redstart; a bird that is endemic to Northwestern Africa and is only recorded in Europe (including Malta) as a vagrant (very rare) bird and a Rustic Bunting, a bird that breeds in the extreme limits of Northeastern Europe and again is a very rare bird in western European countries like Malta. Coincidentally, these two birds, coming from two opposite corners of the Western Palearctic Ecozone (in brief, an ecozone or a biological realm is a bio-geographic region that contains terrestrial species which seem to have evolved together, separated from other regions by natural barriers such as oceans, mountain ranges and deserts), were recorded on the same day – the 23rd of October.

On the 18th of October, a Meadow Pipit carrying a ring from Norway was caught.

One of the main objectives of bird ringing is to be able to track, through re-captures, the movement of birds, both within a country or more importantly like in this case between countries. Two birds ringed in Comino this season have already been re-trapped in other parts of the Maltese Islands; a Dunnock has been re-trapped in Gozo 14 days later whilst a Robin was re-trapped in Buskett nine days later.

The only two non-passerine species ringed this season were the European Nightjar and the Eurasian Scops Owl, two highly camouflaged nocturnal birds.

BirdLife Malta often organises ringing demonstrations to both the general public and its members so that people can observe the work done by its licensed ringers and enjoy close views of otherwise difficult-to-see birds.

By Nicholas Galea, BirdLife Malta bird ringer

A summary of this report was originally printed in the December 2019 issue of BirdLife Malta’s quarterly magazine Bird’s Eye View